Struck by a brain tumour, she truly grasped how terrifying life can be for the mentally ill

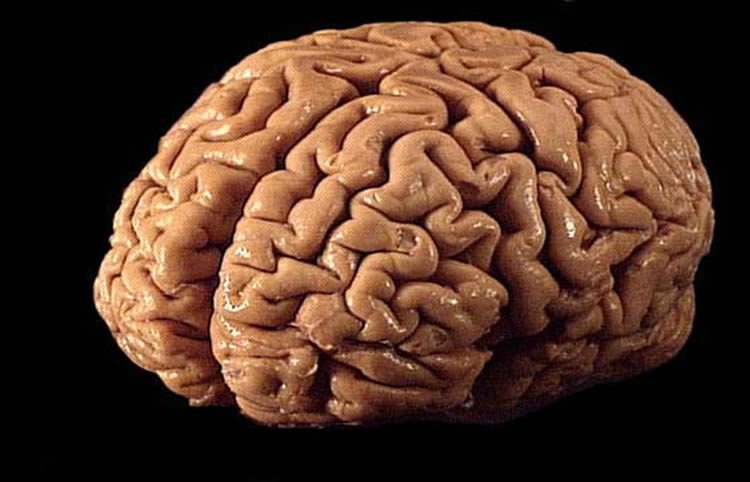

As the director of the human brain bank at the United States National Institute of Mental Health, I am surrounded by brains, some floating in jars of formalin and others icebound in freezers. As part of my work, I cut these brains into tiny pieces and study their molecular and genetic structure.

As the director of the human brain bank at the United States National Institute of Mental Health, I am surrounded by brains, some floating in jars of formalin and others icebound in freezers. As part of my work, I cut these brains into tiny pieces and study their molecular and genetic structure.

My speciality is schizophrenia, a devastating disease that often makes it hard for the patient to discern what is real and what is not.

I examine the brains of people with schizophrenia whose suffering was so acute that they committed suicide.

I always did my work with great passion, but I don’t think I really understood what was at stake until my own brain stopped working.

Early last year, I was sitting at my desk when something freakish happened. I extended my arm to turn on the computer and, to my astonishment, my right hand “disappeared” when I moved it to the right lower quadrant of the keyboard. I tried again, and the same thing happened: The hand disappeared completely as if it had been cut off at the wrist. Stricken with fear, I kept trying to find my right hand, but it was gone.

I had battled breast cancer in 2009 and melanoma in 2012, but I had never considered the possibility of a brain tumour. I knew immediately that this was the most logical explanation for my symptoms, and yet I quickly dismissed the thought.

Instead, I headed to a meeting with my colleagues. We were supposed to review new data on the molecular composition of schizophrenia patients’ frontal cortex, a region that shapes who we are – our thoughts, emotions, memories.

But I couldn’t focus because the other scientists’ faces kept vanishing. Thoughts about a brain tumour crept quietly into my consciousness again, then screamed for attention.

An MRI scan later in the day showed that I indeed had a small brain tumour – it was bleeding and blocking my right visual field. I was told it was metastatic melanoma and was given what was, in effect, a death sentence. I was a scientist, a triathlete, a wife, a mother and a grandmother. Then one day my hand vanished, and it was over.

Almost right away, I had brain surgery, which removed the tumour and the blood. I quickly regained my vision. Unfortunately, new lesions were popping up throughout my brain, small but persistent. I started radiation treatments. In the spring, I entered an immunotherapy clinical trial. Shortly before the end of this treatment, my brain really went awry.

It was difficult, at first, to pinpoint the changes in my behaviour because they came on slowly. I didn’t suddenly become someone else. Rather, some of my normal traits and behaviours became exaggerated and distorted, as if I were turning into a caricature of myself.

I had always been very active but, now, I was rushing about frantically. I had no time for anything – not even for the things I really enjoyed, like talking to my children and my sister on the telephone. I cut them off mid-sentence, running off somewhere to do something of great importance, though what exactly, I couldn’t say. I became rude and snapped at anyone who threatened to distract me. I would read a paragraph and forget it instantly. I got lost driving home from work along a route I had taken for decades. I went running in the woods outside my house, barely dressed.

Yet, I wasn’t worried. Like many patients with mental illness, whose brains I had studied for a lifetime, I was losing my grasp on reality.

I came up with elaborate justifications for my behaviour.

I had reasons for everything I did and, even if I couldn’t articulate these reasons, my certainty that they existed reinforced my belief that I was perfectly sane.

I kept sending my doctor detailed e-mail about how great I was feeling. I was excited that I had completed immunotherapy. I felt certain that there was nothing wrong with my brain. This wasn’t just wishful thinking or extreme denial; my world view made perfect sense to me. I still saw myself as a scientist – a master of the rational – and was, in fact, still working hard on other people’s brains, not able to see that my own was crashing.

One day, when I was acting particularly strangely, my family took me to the emergency room. A brain scan showed many new tumours, inflammation and severe swelling. My frontal cortex was especially affected. I had studied this area of the brain for 30 years; I knew what that kind of swelling meant, and yet I showed no interest in the scans. Instead, I believed that my doctor and my family were scheming behind my back and making a mistake by giving in to unreasonable panic. I was frustrated that no one saw the world as clearly as I did.

Despite my conviction that there was nothing really wrong with me, I took the drugs prescribed. Steroids reduced the swelling and inflammation. Then the visible tumours were destroyed by radiation. I was also placed on a new drug regimen intended to kill the melanoma cells in my body.

Gradually, my brain began to work again. Memories started coming back, as if I had awakened from a deep sleep. I could tell the days apart. I could find my way home from work. I began apologising left and right for my strange actions and insensitive behaviour. But the more I remembered, the more frightened I became that I might lose my mind again.

The underlying causes of mental illness are rarely as clear as metastatic brain cancer. And yet I felt I understood for the first time what many of the patients I study go through – the fear and confusion of living in a world that doesn’t make sense; a world in which the past is forgotten and the future is utterly unpredictable. I had tried to fill the gaps with guesses. But when my guesses were wrong, conspiracy theories crawled in.

As terrifying as it was for me, it was even more terrifying for my family. For them, it was not just the prospect of my death that was shockingly painful, but the possibility that my persona, who I was – my brain – might change so profoundly that I would, in effect, vanish before I was truly gone. Or as my daughter put it: “Mum, I thought I had already lost you.”

My latest MRI scan shows that almost all the tumours in my brain have disappeared or shrunk considerably. Against all odds, the combination of treatments has been effective. I still scrutinise my emotions and behaviours, examining my mind over and over for any loose ends. It remains an obsession.

But I am learning to delight in the fact that my brain works again. I can see the sunny street outside and make total sense of it. I can ever so casually extend my arm and call my children, and they will recognise my voice and sigh with relief.

I can flick on my computer and get back to work.

- Barbara K. Lipska, a neuroscientist, is the director of the Human Brain Collection Core at the National Institute of Mental Health.

Taken from StraitsTimes.Com